- Home

- Margot Harrison

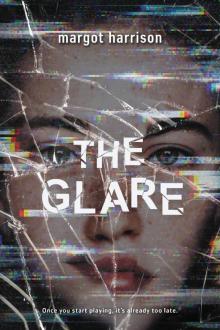

The Glare Page 3

The Glare Read online

Page 3

I’m home.

“You do remember,” Dad says. He reaches out and clasps my hand in his.

By the time we’re inside, I’ve managed to sniffle back some of the tears and wipe my face. Which is lucky, because she comes to meet us—thick black hair in a messy ponytail, black-framed glasses, curvy upper lip. Dad’s new wife, Erika Kim.

We hug but pull out of it quickly. Feeling Erika’s eyes follow me as I move around the living room, I can tell she does notice things.

She looks so young and earnest in her jeans and T-shirt, more like one of the geology students who spent a month digging up our old creek bed than a vain stepmother in a book. But there’s also something wary about her that puts me on guard.

“You look so much like your mom,” she says. “I was going to make tea—would you like some?”

“That would be great.” Control yourself. Smile. Be normal.

On the way to the kitchen, something goes tick, tick, tick, and I stop short.

“Isn’t it gorgeous?” Erika pats the grandfather clock’s oak cabinet. “An heirloom from your great-grandfather, and who knows how much further back it goes.”

“I remember.” The clock pauses solemnly after each metallic tick, as if holding its breath. And now I also remember that when I was little I always thought it was saying, Tsk, tsk, disapproving of me.

As we reach the kitchen, I’m holding my breath like the clock, though I don’t know why. It’s straight out of a home-improvement magazine: glittering granite and stainless steel with older dark paneling on the walls and door frames.

“You redid most of it—not the floor, though,” I say. The tiles are dingy pink gray, just as I remember. A dark splotch draws my eye like a vortex. Drain cleaner. Blinding. Blood.

Stop being silly. The babysitter didn’t hurt herself in our house. I sink into a chair, my T-shirt suddenly sticky, my heart thumping.

“Floors are next on the list,” Erika says, shoveling leaves into a teapot. There’s still a tension in her spine, a watchfulness, as if my presence has changed this beautiful house for her and she’s not sure why.

When she clicks on the gas burner, something clicks in me, too. Hedda, what were you thinking? This house could have burned to the ground!

It’s Mom’s voice. I close my eyes, shocked by the waves of guilt that fill me along with a rush of memory. The whiff of gas in the air is pure shame. I did it. I turned on the burner and let it hiss. Mom was so angry.

“This house is so old,” I say, fighting my urge to jump up and flick off the burner. “I didn’t remember that.”

“Craftsman, 1909.” As Erika brings us a steaming tray, Dad launches into a lecture about their latest renovations.

My face stiffens into a mask: nod and smile, nod and laugh. I want to be happy for real, but it’s all just too new, and the stakes are too high.

“Are you going to pick up Clint?” Dad asks Erika.

My nine-year-old half brother, a complete stranger to me. My heart thuds at the thought that he might look at me for the first time and see a freak, an intruder.

“Conor’s mom’s giving him a ride,” Erika says.

“Where does Clint go to school?” I clasp my hands to stop the trembling.

That turns out to be the right question to ask; Dad and Erika rhapsodize about the nearby elementary school with its “holistic curriculum.” “They grow their own lettuce and feed chickens,” Erika says.

Do they slaughter, pluck, and stew chickens? I know all about that. But I smile back—normal—as she says, “We’ve heard good things about the high school, too.”

Dad clears his throat. “Not that you’ll be going there. I assume you brought your study materials.”

Fortune favors the brave, right? “I’d love to try out regular school, actually. I’m curious about AP classes.”

Dad looks confused. “Jane said—well, you did bring your homeschooling stuff, right? At schools around here, kids use computers, and—”

“You can get special accommodations to learn however you need to. I read that in the New York Times.”

The doorbell rings, and Erika springs out of the kitchen.

“You’d really want to enroll in school here?” Dad asks.

I feel light-headed, like I’ve snuck beer from a discarded can at the fair. “It’s just an idea. That way Mom could stay in Australia as long as she needs to. And it wouldn’t cost you anything if I went to public school, right?”

“Cost’s not the issue.”

But before he can continue, Clint shuffles into the kitchen. He looks like a mini Erika with Dad’s wavy, tousled hair, and his eyes are glued to his phone.

Erika whispers in his ear. Clint lowers the phone and solemnly says, “Hi.”

“Hi.” I grope for something he and I could have in common. “Is that your bike in the garage? Pretty cool.” My own rusty bike was barely adequate for getting around the ranch, but it gave me distance from Mom when I needed it.

Clint speaks in a drone, eyes back on his screen. “It’s a mountain bike. I got it for my birthday, and I can’t ride it yet, because we don’t have time to go to the mountains.”

When his mom releases his shoulder, he bolts, his footsteps pounding upstairs.

“He’s shy,” Dad says.

“We’re working on his social anxiety.” Erika clears her throat. “Maybe we can hit the trails before school starts. You could help teach him.”

If Mom were in Erika’s place, she’d keep Clint close and not let me near him. Erika’s shy, too, but she’s reaching out, almost like she’s lonely. I feel a sudden rush of gratitude toward her.

She follows Clint upstairs, and my dad excuses himself to make up my room, so I set out to see how much of the house I remember. The living room has been renovated into magazine perfection, but I recognize the narrow, sun-flooded passage running along the back of the house, and the little room beyond—Dad’s study. Once his sacred domain, now it’s a storage space crammed with packing boxes. The desk is dominated by a giant flat Glare-screen, but it’s not lit up.

The walls are clean and white, yet half-formed memories darken them like smoke blurring a landscape. I wasn’t supposed to go in here. I did something bad—what?

I bend over the desk, where Dad has lined up framed photos: Mom and me, just me, him and Erika, him and Clint and Erika. None of him and me. Those two sun-faded people must be his parents, whom I’ve never met. They’re barbecuing on a cement-block porch, the man raising a Budweiser. Beside that is a photo of a small boy, fishing pole in his hands, caught in the glitter of sun off a lake. A hand rests on his shoulder, but the rest of the image has been sliced away. I lean closer.

“Hedda?”

I back away like Dad’s caught me at something. “I wanted to see how much of the house I remember.”

“Let me show you the rest.”

He shows off the tiny but breathtaking bay view, then ushers me up the majestic, dark-paneled staircase. “Your stuff’s already in your room.”

Fizzy sounds echo in the hallway, and Clint’s half-open door reveals an enormous Glare-screen. Bizarre shapes in wild colors flit over it, making me blink but not look away. That’s control, too.

Dad pulls the door closed. “He’s in a pretty serious gaming phase. Erika was worried about his screen time, but the one he’s most hooked on is recommended by his school for the educational content, so we’re letting it slide for now.”

Hooked. Addicted. I want to tell Dad I understand what he’s talking about, having read newspaper articles on the “screen time” debate, but before I can find words, I’m standing in my room. My room.

It’s different. The toys that used to cover the floor have given way to the staid maturity of a guest room. The princessy purple-and-gold bedspread and curtains are gone, replaced by crisp cream-and-green cotton.

But the gabled ceiling still slants over the bed, making it feel enclosed and protected. The window still looks out on the street, with its sh

immering cottonwoods so close together they could be one continuous tree. Towering built-ins still hold my stuffed lions—a pair, male and female—my unicorn figurines, and—

“Oh.” I fall to my knees to leaf through my childhood books. Each illustration strikes bells in my memory: the twelve dancing princesses discarding their worn-out slippers; Mr. Toad joyriding in his motor car; Hugo Cabret working the gears of the gigantic clock.

Dad kneels beside me, looking over my shoulder.

“I never read these to you,” he says as I slide D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths back on its shelf. “I was working insane hours in those days. One of the things I regret.”

He cares. I say, “Me too,” rising and plopping my backpack on the bed.

Dad’s voice wobbles. “Hedda…”

“What?” I glance at the door. No sign of Erika.

My father takes a deep breath, then fixes his eyes on mine. “Hedda, what did your mom tell you about why she brought you to Arizona? Or maybe you remember?”

I sit on the bed and hunch into my hoodie, drawing the sleeves down to my fingertips. If I use the word “Glare,” he’ll think I’m still six. “She said—well, there was that thing with the babysitter, and then I got scared of screens, so Mom took them all away, and I…” Freaked out. Went off-kilter.

Dad winces. “That poor Westover girl. Jane liked her a lot, and she never quite recovered from what happened to her.”

To the babysitter. Not to me. Does he not remember the bad things I did, or is he just being polite?

Or did Mom not tell him?

Dad’s still talking: “That’s when your mother decided screen culture was hurting people, especially young people. Me, I’ve always believed technology reflects us. It can hurt or heal or be completely neutral, depending on what—”

“I know. I’ve read all about it.” It’s an enormous relief to be honest with someone. “I know Mom isn’t the only person who thinks screens are dangerous.” The devil. Crack cocaine. Those are just two of the things parents compared the Glare to in an article I read called “Silicon Valley’s Elite Are Shielding Their Kids from the Tech They Created.” “But most of those people… they worry about young kids. Not teenagers.”

Dad cocks his head. “And do you feel like screens are dangerous?”

Being asked for my opinion brings a flush of warmth to my chest, then to my face. “I don’t really know,” I say in a small voice. “But I think I could manage the Gl—screens. I don’t think they can make someone hurt herself. Not without help from her own brain.”

Dad fumbles in the pocket of his sport coat. “I realize your mother can be… adamant, Hedda. But she does love you, and you’re sixteen. I told her I’d keep your tech exposure to a minimum. I even installed a landline so you can talk to her.”

My heart sinks—then does a roller coaster loop as I see what he’s holding out to me on his palm. A sleek sliver of metal—a Glare-box! No, a phone.

“But—”

“But this is for you.” He places the phone in my palm—smooth, heavy, alive. My pulse thumps so hard it’s a struggle to focus. “It’s strictly so I can find you if you go missing. I’ve set it to block all numbers but mine and Erika’s.”

I stare at the shiny dark screen, knowing from watching other people that one press of the single button will light it up. Control yourself. “You don’t want me to… use it?”

Dad’s face is serious, but there’s laughter in his voice. “Do you know how?”

I blush again. “No.”

“Hedda.” His smile creeps out now. “You’re acting like I’ve asked you to disable a bomb. All you have to do is carry this every time you leave the house. If we call you, you’ll see a flashing light. Press the button on the screen that says accept. And if you’re lost and need to get in touch—well, I’ll let Erika show you the rest. There’s a data plan, but you won’t need it.”

I’m holding a cell phone. I’ve seen how other people cradle theirs, like it’s their most precious possession. My mouth goes dry as I realize he’s trusting me with the Glare.

“Thank you,” I manage to say.

Dad touches my shoulder. His eyes are so different from Mom’s and mine, layered with green and gold like trees starting to turn. “This isn’t a license to break all your mom’s rules. But sooner or later you’ll need to make your own choices, won’t you?”

My fingers close around the phone, hard. “I want to go to college. That’s why I asked about school—because I want to be like you someday.”

“All these years,” Dad says in a low voice, “I’ve thought of you out there in the desert, Hedda. Leading such a different life from us, like an early settler on the wild frontier, wiry and strong and tanned and fearless. Sometimes I’ve wished Clint could have that life. Sometimes I’ve envied you.”

I let out my breath, afraid to break the spell. Not knowing how to explain that I don’t feel fearless or enviable today.

He bends to hug me. “Maybe I didn’t know you as well as I thought. Maybe we can do something about that now.”

The phone is caught between us, and I swear it hums in my palm. I don’t pull away.

When he’s gone again, though, I don’t know what to do next. The phone thrums almost imperceptibly with the power it carries. It wants to harvest signals from the air and connect, connect me, and I don’t know how to be connected. I want to be, but—

I hide it on a shelf in the walk-in closet under a pile of sheets and pillowcases. If it hums or flashes now, I won’t know. It can call to me all night—I don’t care.

Something’s moving in the closet.

The sound hovers on the edge of awareness, like tree branches rubbing in the wind. I sit upright in the pearly-blue Pacific dawn, staring at the half-open door. I woke several times in the middle of the night, thinking I heard the Glare-box ringing like our phone at home, but it wasn’t, of course.

I rise, the hardwood cold on my bare soles. The closet is dead still now. I lift the sheets to check the phone, but it’s a silent, shiny brick.

I kneel to explore the narrow crawl space at the back of the closet, where I find a shoehorn, vacuum cleaner hoses, and—something soft. A Raggedy Ann doll in a dirty-white pinafore.

Found you. For ten years she’s waited alone in the dark for me. I lift my abandoned doll into the light, remembering her soft weight, her heedless thread smile—and freeze. Her button eyes are gone, leaving only snips of thread.

A chill goes through me, and I almost drop her. Did I do that?

Maybe it was just wear and tear. Her face has a dark patch around the mouth where I used to feed her (or try to), and I certainly don’t remember cutting her eyes off. But the more I stare at her, the more I think I was trying to do to Raggedy Ann what the babysitter did to herself. To shield her from seeing something terrible.

I stow the phone in my backpack with a sweater and hoodie on top to muffle any sounds. Then I bring the backpack down to breakfast—which is lucky, because Erika asks for the phone to “show me the basics.”

When she presses the button at the base, I tingle all over, but I don’t look away. This is part of control. The screen is hard under my fingertips, yet it responds to my touch like something alive. Erika shows me how to enter a password. When I get it right, the screen blooms with all the colors of the rainbow. Tiny birds fly to roost, then turn into pictures like heraldic coats of arms.

Magic. It’s Christmas morning and Fourth of July fireworks rolled into one, and I’m shaking, staring, doing my best to concentrate as Erika shows me how to call her or Dad. It’s almost a relief to put the thing away again. Seeing someone else’s screen is one thing, but there’s something about touching my screen, giving it commands, that I could get too used to.

The dizziness doesn’t go away until Erika takes Clint and me to the downtown farmers market, where I breathe in straw and overripe berries and frying tortillas. I stop at a stand where a girl my age in a sundress is selling leafy greens, ta

pping on a phone.

I pick up a bunch of chard, admiring the red veins, and ask her about planting times and mulching methods. She answers me, the phone alive in her hand the whole time, and I want to ask how she manages to live in both worlds, but I don’t dare.

“Look at these,” I tell Erika, pointing to the speckled heirloom cherry tomatoes. “With those serranos, they’d make a great chili.”

She smiles in a sly way I haven’t seen before. “Are you offering to cook?”

“Could I?” Itching for chores to do, I grab a paper sack for the tomatoes. “I make it at home all the time.”

“I was kidding!” Erika swivels to keep an eye on Clint. “But if you actually want to, I won’t say no.”

After the market, we spend the afternoon at the beach. Clint complains when Erika makes him leave his Glare-box—a tablet, it’s actually called—in the car.

When he walks out into the surf, I follow at a distance, still trying to get used to this vast watery commotion I loved as a kid. It smells fishy. I pass a girl in a glossy peony-pink bikini and wonder how that would look on me. Or maybe the leopard print? No, something in between.

Clint walks backward toward me. “You won’t drown. I used to be scared, too.”

“I’m not scared.” His face closes up, and I change my tone. “Can you show me how to ride the waves like you do?”

Now he looks earnest, just like Dad. “Watch me.”

By four, we’re both salt-caked and sunbaked, and my brother has smiled at me once. He seems to have decided I’m not a blood-thirsty ogre, and that’s a start.

Back home, Clint actually skips up the steep steps from the sidewalk, humming under his breath. At the top he stops abruptly and says, “Hi, Mireya. Why are you here?”

Mireya? At the ranch, I imagined this moment over and over—what I’d be wearing when I saw her again, what she’d be wearing, what we’d say. Now it’s all happening much too fast, and my throat cinches shut, leaving me speechless.

The Glare

The Glare The Killer in Me

The Killer in Me