- Home

- Margot Harrison

The Killer in Me Page 6

The Killer in Me Read online

Page 6

I’d never gotten a note at school that said anything good. I almost threw it away unopened, but curiosity won out. Standing at my locker after the bell, I deciphered a message written in silvery-purple ink and scrunched, adult-looking cursive: Your book sounds good. Can I borrow it? NB.

The class had two NBs, but I knew Ned Bissette hadn’t written this. The paper wasn’t perfumed or anything—just a ratty scrap from a notebook—but everything about it said special and girl.

I slipped the note into my cherrywood box at home, where I collect wheat pennies, and tried not to think about it. Because she had no dad, Nina Barrows was vulnerable, a semi-outcast like me. Maybe a popular girl had bribed her to lure me in with fake friendship overtures that would tempt me to do something mockable. Paranoid, yes, but this was middle school.

The Dick book stayed in my backpack. Next English class, I sat behind Nina and one row over. She wore a deep blue sweater that was almost purple, like her ink, and a sparkly clip like stars against her black hair.

I set the book on my desk, covering the author’s last name with two pencils. I probably would have continued to do this every class until the semester ended, not daring to speak a word, if, when the bell rang, Nina hadn’t turned and smiled at me.

Next thing I knew, the hardcover was in her hands, pressed against her soft ultramarine sweater, and I was looking right into her strange, beautiful eyes. How’d I never notice them before?

“I liked it,” she said a week later, returning the book. “I like how the main guy, he thought he was being good and going along with the rules. But part of him wanted to break them.”

Something swelled in my chest. I was the guy in the book, sticking to the straight and narrow—because my mom needed to have one kid who was never arrested—while something deep inside me yearned to raise hell.

How had she known? Did she want to raise hell, too?

We didn’t talk much about ourselves, Nina and I, even when we started hanging out after school. Books were safe, movies were safe, making silly videos with our phones was safe. The other kids could look at us and see two nerds doing nerd things, not a guy with a desperate crush on a girl.

I was still petrified the first time she invited me home. We’d been to a comic-drawing workshop at the library, and she lived just up the hill. But was this a date? A study date? What if her mom was there? Would I see her room? If she sat on her bed, should I sit down with her?

Nina’s mom worked most afternoons, it turned out, and we played with her cat and watched old movies—never on the same couch. Teasing each other about hot actors and actresses, most of whom were now old or dead, was the closest we got to romance.

We memorized every smart-ass high school movie ever made and thought we were so freaking mature and superior—middle school dating, what a joke.

I knew I couldn’t tell anyone I just liked being near Nina. For now, that was enough.

By the time I got up the courage to invite her to my house, it was winter of eighth grade, and I used the excuse of cutting the Christmas tree. We went out to the woods with my mom, who seemed to like Nina. “She’s quiet, but you can tell she’s thinking,” she said.

A few months later, though, when she picked me up from Nina’s house, my mom gave me a strange warning. “That girl isn’t going to stick around here after high school, Warren. She’s not the type.”

“I know that.” Nina and I had extensively discussed our futures, which included film school in New York or LA for me and some fancy advanced degree for her so she could work at the American Museum of Natural History.

Then I realized my mom thought I would stay “around here.” She didn’t want me to be disappointed when Nina flew away somewhere glamorous and never returned.

After that, I didn’t talk to Mom about Nina. But I did invite her over one more time, during mud season, which is when everything went to hell, thanks to Rye.

Then again, maybe I’m giving Rye and his dickishness too much credit. Because that was when Nina started acting weird, and not just to me.

For a few weeks after that disastrous Saturday, we still talked, but Nina didn’t invite me over, and gradually she stopped sitting next to me. When I approached her, she smiled and said hi, but her eyes darted away.

Looking back, I know it wasn’t just about me or us. Nina developed a waxy paleness and deep circles under her eyes that spring; she missed a whole week of school. I should have asked her what was wrong. But self-centered eighth-grade me thought if she wanted to avoid me, two could play at that game.

I told myself I was making a heroic display of pride, when I was being almost as big a dick as my brother.

Two years later, when Nina came to me for the pills, we were like strangers. She wore dangly earrings and a red scarf that day, and I wanted to wrap my arms around her.

I wanted to say, “Do any japing lately?”

I wanted to ask if she ever finished East of Eden.

I wanted to tell her, “Don’t do this. You’re smart enough already.” I wanted to warn her about the headaches, the nervousness, and the other side effects I’d only read about, because I refused to try the stuff myself.

It was her choice, I finally told myself as I took her twenties and doled the pills into a sandwich baggie. Free market, supply and demand.

I profited from her bad choices, over and over. I was secretly relieved when she told me her mom had found her stash, even though it meant I might not see her anymore.

Now I realize that whatever happened to Nina in eighth grade, it’s not over. And study drugs were only the beginning.

“So?” I say now. “Please don’t tell me that dude we chased in the Sequoia was your biological father.”

She’s lied so much. I try to imagine myself cold and silent like early Clint Eastwood, hard-nosed like Philip Marlowe. Accepting no unlikely stories from dames in distress. But I just feel lost.

Nina is scrunched down in her seat, looking out the window. The wind grabs a tendril of black hair and whips it over her eyes, and I resist the urge to smooth it back. She looks so fragile, so defeated, and I hate how that sight hollows out a space in me. I want to put my arm around her. Last night she almost seemed like she would have let me.

Until she went batshit and attacked me in her sleep.

She says in a small voice, “My birth mom doesn’t actually live here. She’s in Arizona.”

“So.” I try to keep my own voice level. No accusing or whining; I’m a detective or a shrink, getting to the truth. “The whole thing was a lie.”

She doesn’t answer.

“Whose house were we at?”

“The Gustafssons’.”

“I know, but who the hell are they? To you, I mean.”

“Nobody.” Even softer: “I think they’re dead.”

It takes all three hours of the drive home, with lots of stops and starts, for her to talk.

I gather this much: Mr. and Mrs. Gustafsson live in that house—or lived. They didn’t answer their door last night because the driver of the Sequoia abducted and killed them. So she says.

Does she know the Gustafssons? No. Does she know the driver of the Sequoia? No. Wait, maybe she does. “In a way. I knew he’d do this.”

“What do you mean, ‘in a way’?”

She looks out the window. “You wouldn’t believe me.”

I promise her I would believe her, though I’m not sure.

“It doesn’t matter. It’s over now.”

She just keeps repeating that, in a dead voice that reminds me of the traumatized final girl at the end of a horror movie. Her face is turned from me, but I suspect there are tears.

“If people got killed, it matters a lot,” I point out, getting impatient.

Stop being an asshole, Warren. Nothing happened in Schenectady. Nobody got killed. Nina’s been lying to me since yesterday afternoon, maybe without knowing she was. She could have a serious mental illness—a psychosis—and I’ve been enabling it by obeying he

r orders, by chasing the Sequoia, by asking these questions. She needs meds, maybe hospitalization. Doctors, her mom. Not me being all up in her face.

“I don’t want to get you any more involved. It’s dangerous.”

Her head’s bowed so her hair covers her face, and I can tell she believes what she just said. Behind her, white pines file past under a sky full of fat-bellied rain clouds.

What’s wrong with you? I plead silently. Why can’t I help?

I’ll have to call her mom, tell her what happened, find out if Nina’s already getting treatment. It’s a betrayal, an ugly one, but the alternative is watching her spiral deeper into her own terrors. Or abandoning her—again.

I shouldn’t have sold her those pills. Dick move, Warren. If only I could take it back, all of it….

“Thank you,” Nina says when she drops me off. “Thank you, Warren.”

Like last night. Only this time she isn’t holding my hand.

I watch her switch over to the driver’s seat, watch her drive away. I calm my dogs. I go inside, fall on my bed fully clothed, ignore my mom’s questions about how I just disappeared yesterday.

I can’t call Nina’s mom yet. I’ll need rest for that. Right now I can’t seem to convince myself there’s no alternative.

When I wake up, it’s dark and I can hear the radio downstairs.

And I remember something.

Write it down this second, or you’ll forget. I grab a piece of notebook paper and a pen and scribble the sequence of letters and numbers in my head: DP6K62.

The Sequoia’s license plate. I didn’t exactly try to memorize it, but numbers stick in my brain. The two might be a three, but I’m sure about the rest.

I don’t call Nina’s mom on Saturday, or on Sunday, or even on Monday.

I can’t do it. I don’t want to do it. All I can see is the expression in Nina’s eyes when she thanked me for driving to a stranger’s house and chasing another stranger’s car. Like I was the only person she could trust.

So I keep making excuses. On Sunday and Monday, I even go online and search “Gustafsson” and their address. Aside from an old article about animal abuse at the slaughterhouse that Mr. Gustafsson manages, no news items come up; no one has murdered them.

I have AP English with Nina, but I sit in the back row and don’t look at her. I keep blinders on in the hallway and avoid the woods behind the soccer field. A new kid asks me for painkillers, and I text him my brother Gray’s number and say I’m out of the business.

I started selling because I wanted to save enough for a non-beater car. Now I just want to apply to college without a rap sheet.

An awful thought keeps nagging at me: Did I help make Nina this way? Crying out in her dreams, seeing killers on sleepy streets? Could this have started with a drug interaction, or the amphetamines loosening her grip on reality?

I research “stimulant psychosis.” People get it when they’re abusing or overdosing, and I didn’t see Nina pop a single pill on our trip. Unless—maybe in the restroom?

It rains all week. Mud sluices down our road; the brook jumps its banks. Downtown, sewer water pours into basements. I hope Nina’s house is okay.

I remember how her hand felt in mine, and how she breathed softly and evenly as she slept beside me—in a Subaru, fully clothed, ten minutes before she woke up screaming and trying to brain me with her elbow. But still.

I keep on researching. Just in case.

It takes me four clicks to find out the New Mexico DMV doesn’t trace plate numbers for free. You have to pay a private-investigation firm and assure them you have a legit legal reason to want the driver’s name and address. Nobody checks up on whether you actually do, and the PI company promises you the specs within a day.

Maybe my dad’s right when he says we might as well all be crapping out on Main Street, because privacy doesn’t exist anymore.

The trace costs barely more than an oil change, but I don’t have an online payment account. I could ask to use Rye’s—he’s got several, most of them untraceable, that he uses to buy fake IDs for him and his friends. To hear him talk, he’s a digital con man.

I hate asking my brother for anything, but I’d hate calling Nina’s mom more.

I’ll think of a story to tell him. I don’t need to hear Rye’s thoughts on Nina’s degree of hotness; his porn-derived standards can’t touch her. Nina reminds me of the pre-Raphaelite girls in my Brit Lit textbook with their pale skin and glowing eyes and acres of hair that waft around them like seaweed. (Except hers just hangs.)

Her eyes, I swear, are bronze. A hazel brown that’s weirdly pale and luminous against her black hair; in some lights, they look almost amber.

And she’s sick, I remind myself. She needs your help.

Enough of being pathetic. What’s happening with the Gustafssons of Schenectady these days? I haven’t bothered to check in on them in a while, so I do.

Shit.

On Friday, I catch Nina in the hall, walk right up to her, and practically pin her against her locker. “We have to go to the cops.”

Her eyes widen like she has no idea what I’m talking about, and she inches away from me.

I snatch my phone from my pack, wake it, and hand it to her. “You knew.”

Starting Wednesday, the headlines have been all over the Schenectady papers and TV. “Schenectady PD Seeks Information on Missing Couple.”

Ruth and Gary Gustafsson didn’t show up to their jobs on Monday, and Mrs. Gustafsson’s brother called the cops. The glass in the door from the garage was broken. The couple’s Hyundai is missing, but they didn’t take their suitcases or their medications. They have grown kids, big families, lots of friends, all of whom say it just doesn’t look right.

My browser loads the official MISSING poster. “Look at them,” I say.

They’re both big, gentle-looking people. Mrs. Gustafsson wears a sleeveless shirt that doesn’t flatter her in the photo, and Mr. Gustafsson has a comb-over. His arm’s around her, and the affection looks real.

I show Nina the bookmarked articles one by one. Mrs. Gustafsson fostered Humane Society kittens. Mr. Gustafsson worked at a slaughterhouse, but his friends describe him as the kindest person they knew. One commenter speculates that an animal-rights group targeted him after a guy on his crew was arrested for skinning a calf alive, but Gustafsson himself wasn’t implicated in the cruelty.

Nina’s mouth twists as she reads, and her eyes get big and wet.

“Say something,” I say.

I was so upset last night, after I found this stuff, that I almost called her. I considered driving over to her house unannounced. Instead, I ended up spending most of the night online, hogging our crappy connection. With Rye’s help, I ordered that trace on the license plate, then jittered through first period wondering what to say to Nina.

Words still fail me. I thought you were crazy, but now I’m starting to think you’re actually an accomplice to…abduction? Murder?

Articles and police alerts are one thing. When I watched the videos, the bottom dropped out of my stomach.

I saw the block we drove on. The house where we parked. It looked different in the sunlight with police tape all over, but I was sure.

In every story, I waited for the reporter to mention a neighbor who noticed a Subaru with Vermont plates lurking outside the Gustafssons’ house on Friday night. To say the police were seeking info on the mystery car.

Nothing.

The cops haven’t mentioned a lead or a suspect. Foul play remains just one possibility. Nobody can even put a date to the Gustafssons’ disappearance—except, I guess, Nina and me.

Or just Nina. Technically, they could have vanished Friday, Saturday, or Sunday. How can I be sure she was with me when it happened? It sounds ridiculous, but how do I know she didn’t go back to the city and make it happen?

“I didn’t expect her to look so sweet,” Nina says, still staring at the MISSING poster. A tear rolls down her cheek, and she rubs it away li

ke she’s not sure what it is. “The only time we talked…we got off on the wrong foot, I guess. She thought I was a prank caller.”

“Talked? To who?”

She points to Mrs. Gustafsson. “She had a right to be suspicious. I called her out of the blue.”

“You called her?”

“I tried to warn her. I used a pay phone.”

I grab the phone like it might burn Nina, my gaze darting over the kids rummaging in lockers up and down the row. Did anybody hear that?

If they did, they couldn’t care less. They probably can’t even pronounce Schenectady or find it on a map.

“You’ve seen all this stuff already,” I say, suddenly realizing it. “All these articles.”

She nods. “It’s just different now—talking about it with you.”

I lean in too close to her. With her splotchy cheeks and startled, red-rimmed eyes, she looks like a stranger.

“Who is he?” I whisper.

She shakes her head like she’s confused.

“The guy you think did this. The guy you know ‘in a way.’ Who is he?” As I say the words, I realize what “in a way” might mean. “Is he somebody you don’t know in person? Did you meet him online?”

She’s edging away from me again, fresh tears welling in her eyes.

I follow her. “You have to tell somebody, Nina.”

“I can’t.”

She grabs her backpack and runs, leaving me staring at the Gustafssons’ happy faces as the bell sounds.

I’ve always liked playing detective. Those old-time PIs Sam Spade and Mike Hammer knew how to handle the worst situations—sometimes with fists, sometimes just with a smart-ass remark. And when they encountered a situation beyond repair, they’d light up a smoke or take a swig from their flask and think, What a screwy world. Can’t change it, might as well live with it.

My dad, by contrast, believes in changing the world. That’s why he’s off at a Green Mountain Libertarian Caucus meeting on Friday night, leaving Mom and me to eat dinner alone.

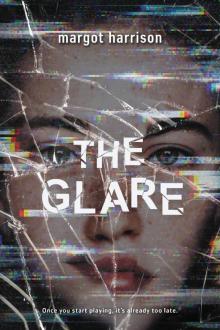

The Glare

The Glare The Killer in Me

The Killer in Me